- November 2016

- President’s Notes

- Better Genetics Equals More Profit

- Thomans Concede Allotments

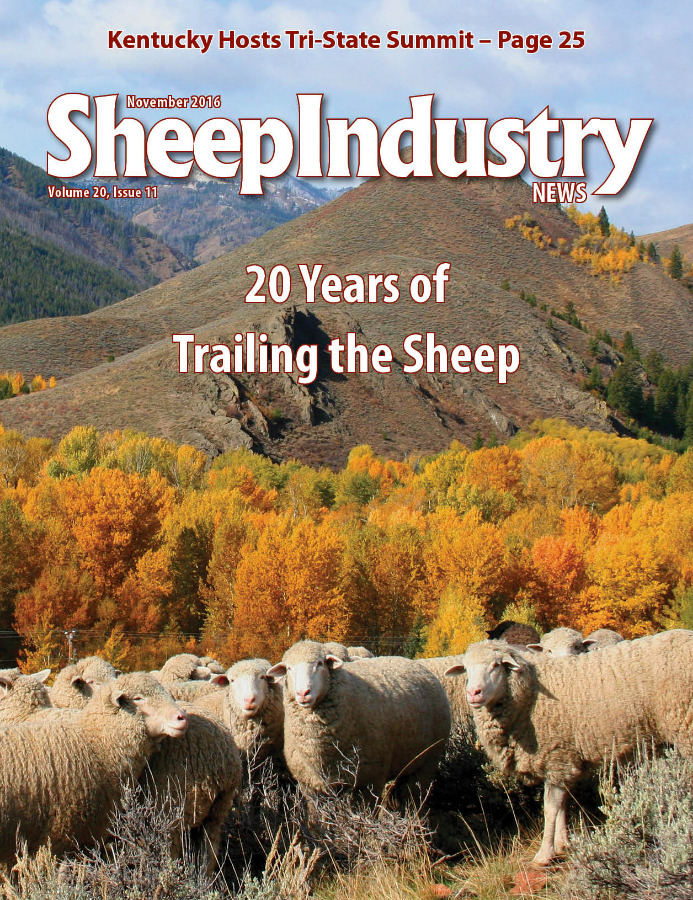

- 20 Years of Trailing the Sheep

- Celebrating Fall at Savage Hart Farm

- New Staff, Consultants on ASI Payroll

- ASI News

- Tri-State Summit Celebrates Growth

- Young Entrepreneur: Matt Anderson

- Knowles Named to Scientific Panel

- Range Productivity Study Complete

- USDA Confirms Screwworm in Florida

- Market Report

- Obituary

Thomans Concede Allotments

CAT URBIGKIT

Special to the Sheep Industry News

Domestic sheep flocks have grazed the Upper Green River region of western Wyoming’s Bridger-Teton National Forest for more than 100 years, but when flocks belonging to W & M Thoman Ranches came out of the mountains at the end of September, the book closed for domestic sheep in this northern portion of the Bridger-Teton.

Long pressured by environmental groups and federal officials, the Thomans at last conceded this fall, waiving their Elk Ridge Allotment Complex grazing permit back to the Bridger-Teton National Forest without preference to another livestock producer. The deal involved a buyout (of an undisclosed sum) of the allotments, and was orchestrated by the Wyoming Wild Sheep Foundation. The Thoman’s fine-wooled Rambouillets had grazed this range for 40 years.

Citing the potential threat of interactions between domestic sheep and wild sheep, and the history of wolf and grizzly bear depredations, the Bridger-Teton National Forest has committed to not allowing the allotments to be restocked with domestic sheep. The agency has indicated it will consider allowing the currently permitted cattle grazing in the Upper Green to spread into a portion of the Thoman allotments “in order to better address ongoing predation issues,” but not until further environmental review is conducted some years in the future.

Citing the potential threat of interactions between domestic sheep and wild sheep, and the history of wolf and grizzly bear depredations, the Bridger-Teton National Forest has committed to not allowing the allotments to be restocked with domestic sheep. The agency has indicated it will consider allowing the currently permitted cattle grazing in the Upper Green to spread into a portion of the Thoman allotments “in order to better address ongoing predation issues,” but not until further environmental review is conducted some years in the future.

The loss of the Thoman allotments – four allotments that grazed up to a total of 3,900 sheep from July through September – is the latest in a series of domestic sheep allotment closures by federal forest officials throughout the West.

The decision to give up the allotments was a difficult one, and one that members of the Thoman family voiced displeasure. Family matriarch, Mickey Thoman, and daughter, Mary, said they believe that the situation had become such that it was best to accept the buyout offer and put their days in the Upper Green behind them.

“I feel in my heart the timing is now or never,” Mary said. “They are running us in the ground.”

The Thomans have spent decades trying to comply with ever-increasing burdensome federal regulations and operating instructions, while adjusting their operations in an attempt to minimize conflicts with recovering grizzly bear and gray wolf populations. For instance, when grizzly depredations continued to rise despite the presence of herders and guardian dogs, Mary took the initiative to begin the use of portable electric pens for the sheep at night. That voluntary action evolved into a mandatory program in which the pens are required every night, and every detail of their use – from how many panels to voltage, from location restrictions to pen movement every night – is determined by a federal agency.

“We’re going to go bankrupt, how much more trying can we do?” Mary asked, noting that federal officials can say that the Thomans weren’t forced off their allotments, but cooperative efforts from agency officials through the years could be classified as half-hearted at best, and hostile at worst.

“We’ve learned how to deal with bears and wolves, but the bureaucrats I haven’t figured out,” Mary said.

The Thomans aren’t sure where they will be taking their sheep for next year’s summer and fall grazing season. Federal officials have been unable to identify currently vacant grazing allotments or grass banks where their flocks would be allowed, and the Thomans are hoping that some of their current cattle permits can be converted back to sheep. Federal land managers are again balking, however, citing concerns for sage grouse and the need to conduct environmental reviews.

Many members of the extended Thoman family, including Laurie Thoman, Kristy Wardell and Dick Thoman were on hand to bring the family’s flocks out of the Upper Green for the last time. Normally this would be a time for celebration as the fat lambs were brought off the mountain, but this year it was a somber affair.

This article is reprinted from the Wyoming Livestock Roundup.