- April 2016

- President’s Notes

- ASI Legislative Trip

- Sage Grouse Discussion

- Changes for Price Reporting

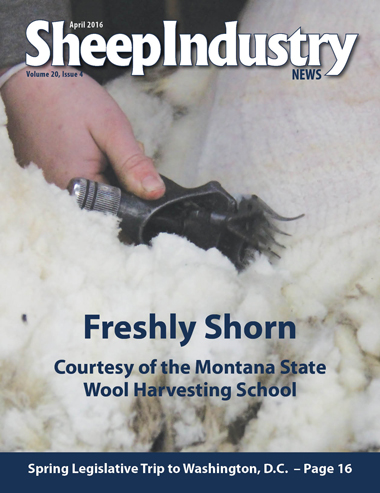

- Shearing 101 in Montana

- Science of Bighorn Report Questioned

- USSES Reports Available

- American Lamb Board Vacancies for 2017

- Market Report

- NLFA Leadership School in Ohio

- Sheep Heritage Foundation Scholarship

- Around the States

- The Last Word

Restaurant Sector Depressed

JULIE STEPANEK SHIFLETT, PH.D.

Juniper Economic Consulting

Lackluster growth in the U.S. restaurant sector has put a damper on the sheep and lamb industry: slowing slaughter rates, filling freezers and weakening live lamb prices. The Daily Livestock Report reported that restaurant industry business conditions deteriorated for much of 2015, saw a modest improvement in January, but were “still notably worse than the same period a year ago” in February, (3/4/16).

The DLR cautions “the fact that restaurant industry performance is not great even with a mild winter and higher disposable incomes should be a significant worry for the U.S. meat industry as we prepare for spring,” (3/4/16).

This year, the lamb industry has had to contend with possibly lower demand, but also the lack of price reporting due to confidentiality. If insufficient packers or volume of lamb is offered in price reporting the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Marketing Service will not report prices for concern that individual packers or trades could be identified and that anonymity couldn’t be preserved. The absence of prices of slaughter lambs in formula/grid trades and for some carcass trades has several unfavorable ramifications for the lamb industry.

First, without key prices the market cannot establish itself, leaving producers and feeders with reduced bargaining power. Second, lack of price reporting of carcass prices further weakens the volume of carcass trades which have served as a basis for pricing formula/grid trades. Third, the lack of prices means that sales of the insurance program Livestock Risk Protection (LRP-Lamb) cannot proceed.

LRP-Lamb Suspended

LRP-Lamb is designed to insure against unexpected declines in market prices. It protects against unexpected downswings in slaughter lambs below an expected price.

The lack of current formula slaughter lamb prices reported is particularly frustrating to LRP-Lamb insurance holders. Indemnities are still paid; however, the actual ending value on which indemnities are calculated is not updated. This means that the current market dynamics – perhaps an additional downturn – are not updated. The insured are paid based upon a rolling average of the last five weeks, whatever prices might have been reported within that period. If no new prices are reported within this period, then the last available price establishes the actual ending value and indemnity payments.

Other livestock risk protection programs such as for feeder and fed cattle and swine rely upon publicly traded futures or options markets to establish the expected prices. However, the lamb industry doesn’t have a parallel futures market. It is for this reason that LRP-Lamb uses industry data from USDA to develop a forecasting mathematical model. A limitation of this method means that it cannot function as designed when prices are not reported. The program is dependent upon weekly USDA reporting.

AMS Making Strides Update Lamb Reporting

USDA/AMS is working closely with ASI and the Livestock Market Information Service to try to improve USDA/AMS reporting in the sheep and lamb industry.

AMS commented, “Since the implementation of Livestock Mandatory Reporting in 2001 and its subsequent revisions, the U.S. lamb industry has become more concentrated at all levels of the production system through consolidation, impacting AMS’ ability to publish certain market information in accordance with the confidentiality provisions of the 1999 Act,” (February 29, 2016).

AMS added, “To help address this issue, LMIC conducted an analysis of the current LMR program for lamb reporting in 2013 at the request of ASI. Based on this study, recommendations were proposed to amend the current LMR regulations to improve the price and supply reporting services of AMS and better align LMR lamb reporting requirements with current industry marketing practices.”

In late January, AMS released an important first step toward improving price reporting in the lamb industry. The threshold for defining lamb packers reporting to the AMS dropped from 75,000 head per year to 35,000 head. The step is an important move toward improving the accuracy of price reporting. It is unclear at this point, however, whether the revision will prevent further price withholding due to confidentiality for formula/grid prices, specifically. The rule takes effect May 31.

Auction Feeder Lamb Prices Strengthened

At the end of February, the USDA/AMS reported that feeder and slaughter lamb trade was seasonably slow. However, feed conditions on the West Coast are being considered as some of the best they have seen in several years (AMS, 2/26/16).

Feeder lamb prices at auctions in Colorado, South Dakota and Texas for 60 to 90 lb. lambs averaged $221.83 per cwt. in February, up 6 percent monthly and 4 percent lower year-on-year.

Only 1,250 feeder lambs traded direct in February, but this came off a surge of 19,000 head traded in January. In February, 400 head traded out of South Dakota for $175 per cwt. at 100 lbs. In Texas, 850 lambs traded at $126.65 per cwt. at 135 lbs.

Slaughter Lamb Prices Lower

January and February slaughter lamb prices were at a three-year low for the first two months of the year.

Live, auction slaughter lamb prices averaged $133.15 per cwt. in February, down 6 percent monthly and down 7 percent year-on-year. Prices were averaged across San Angelo, Texas; Ft. Collins, Colo.; Kalona, Iowa; and South Dakota markets.

Prices for formula/grid slaughter lamb sales were only reported for one week in February. Prices were not released due to confidentiality for the remainder of the month. Slaughter lamb prices on a formula carcass-based sale averaged $282.21 per cwt., down 2 percent monthly and down 9 percent year-on-year. The live-weight equivalent was $141.11 per cwt.

Live, negotiated trades were reported in full in February. Prices averaged $136.03 per cwt., 2 percent lower monthly and down 3 percent year-on-year.

National slaughter rates are relatively low, but sufficiently high to keep Colorado feedlot lambs current. At the beginning of March, 138,720 head of lambs were on feed in Colorado feedlots, down 14 percent monthly and 18 percent lower year-on-year (LMIC from AMS, 3/2016). The number on feed was 10 percent lower than its five-year average. Data on formula/grid slaughter lambs was unavailable for February; however, slaughter lambs that went to harvest on a live, negotiated basis were lighter weight, slipping from 150 lbs. to 141 lbs. monthly.

Pelt Market Lower on Average

Some significant changes to AMS pelt reporting are underway. AMS is proposing to make an important switch from reporting pelt prices and volumes of pelts sold from packers to tanneries to pelt prices paid to producers. The point of sale changed with narrower lines of quality sorts for an improved reporting of the “total value of lambs marketed for slaughter,” – value of the lamb plus pelt (USDA/AMS, 1/29/16).

On Sept. 30, 2015, the Agriculture Reauthorizations Act of 2015 reauthorized the act for an additional five years and includes a provision for adding lamb pelts as a mandatory reporting requirement. Currently, pelt reporting is on a volunteer basis.

Another proposed change to pelt price reporting is to broaden pelt reporting for lambs purchased through a negotiated purchase, formula marketing arrangement or forward contract, compared to only formula-traded lambs currently. Increased volume of pelt reporting will improve accuracy of prices toward a nationally-representative price.

In a rough estimate, the simple average of all unshorn pelts – from Supreme to Damaged/Pullers – fell 11 percent to $2.38 per piece in the five weeks to February 26.

At the end of February, Supreme pelts ranged from $8.50 to $10.25 per pelt and Premium pelts ranged from -$2.00 to $9.25 per piece. A difference between Supreme and Premium pelts is that Supreme are 9 square feet and larger while Premium pelts are 7 to 10 square feet. Further, Supreme pelts carry no discolored fiber. Some discoloration will pull a pelt down into the Premium class.

AMS Price Reports adds Value

USDA/AMS offers a wealth of price information to the lamb industry that can help producers value their product, whether they are selling to a national packer or selling direct to a neighbor or local restaurant. AMS provides prices of feeder lambs, lambs at auction, lamb carcasses, as well as prices for primal and sub-primal cuts. AMS also calculates a cutout value which is a composite of wholesale primal lamb cuts.

The cutout value represents the value of lamb at wholesale. The carcass value – before cutting it into primals – also represents the carcass at wholesale. Some lamb packers use the carcass value as a basis upon which premiums and discounts are added in formula or grid pricing. The carcass market has become rather thin, however. There is some concern that the carcass might not be an appropriate way to value all lambs. The cutout, on the other hand, does represent the wholesale value of all commercial lambs sold.

The gross cutout value is what you would get if you reassembled the primal cuts, such as the shoulder and leg back together to form a complete carcass. AMS explains: The lamb cutout represents the estimated value of a lamb carcass for a given day based on prices being paid for individual lamb items (January 2014).

Each primal cut is a percent of the lamb carcass weight. The rack is 7.70 lbs., for example, out of a 67 lbs. carcass. Or, you could say the rack is 11.00 percent of the total carcass weight. The leg is the largest primal at 31.93 percent of the carcass. The shoulder is the second-largest primal at 23.65 percent. The loin is 11.04 percent. The breast, fore shank, neck and flank make up the balance of the total carcass weight.

The prices of each cut are weighted by their respective lbs. to get the weighted value of each cut. Then the cuts are summed together to get the composite, “recreated” carcass.

In February, the average gross carcass value was $351.23 per cwt. (hundredweight). The cutout is on a per cwt., or 100-lb., basis. If a carcass is 70 lb., then the cutout would be ($351.23 per cwt. X 70 percent = $245.86).

AMS also estimates a net carcass value which is the gross carcass value minus processing and packaging costs of $33.75 per cwt. AMS obtained the processing/packaging cost through a survey of the largest lamb packers.

In February, the net carcass value was $317.48 per cwt., down 2 percent monthly and down 5 percent year-on-year. All primals were down 1 to 2 percent monthly in February.

Compared to a year ago, the leg was 2 percent higher year-on-year, but the shoulder was down 4 percent and the rack was 11 percent off last February’s averages.

Lamb carcass values and the gross carcass value move together. Correlation is 0.99 with 1.0 being perfect synchronization. Since 2005, the carcass value ranged from 79 to 90 percent of the cutout value.

In February lamb carcasses average $357.06, up 2 percent monthly and up 8 percent year-on-year.

Lamb Imports Higher

In 2015, lamb imports were up 9 percent to 178.6 million lbs. Australia’s lamb imports were up 6 percent to 128.2 million lbs. and lamb imports from New Zealand were up 15 percent at 48.2 million lbs.

At wholesale, Australian imported shoulders dropped 3 percent by volume in 2015, while leg imports increased 5 percent and loin imports jumped 17 percent. Australian lamb imports are typically competitive with U.S. product, but there are cases at wholesale where imports come in at a premium.

The Australian shoulder average price in 2015 was 85 percent of the U.S. shoulder value in 2015. The Australian leg was higher-valued than the U.S. leg at 102 percent and the loin was about par, at 98 percent.

2015 Total Lamb Supplies Higher

In 2015, total lamb supplies in the U.S. – including imports – were 3.3 percent higher year-on-year. For the year, lamb imports were up 9 percent and U.S. production was down 3 percent. The lamb import market share grew as a result. In 2014, lamb imports were an estimated 52 percent of total supplies, but jumped to 55 percent in 2015. More than half of lamb in our markets is imported.

Estimates are only estimates, however. We cannot account for the import share sitting in U.S. freezers. What share of imports are actually being sold at groceries and restaurants? Lamb and mutton in cold storage hit a record high of 47.1 million lbs. in February, up 22 percent monthly and 34 percent higher year-on-year.

If the U.S. put all of its domestic production since October into freezers we would still not reach the current volume in cold storage.

Estimated market share estimates also don’t account for domestic lambs that sell outside mainstream commercial channels and are not captured by official statistics. If the estimated 900,000 nontraditional lambs are included in the market share, imports drop from 55 percent to 46 percent of the market, less than half.

Many auction houses across the U.S. are now primarily ethnic markets, of which lambs may or may not be captured in national statistics. South Dakota and Iowa still have traditional auction houses in which the larger, national packers participate. However, auctions such as New Holland, Penn., San Angelo, Texas and Ft. Collins, Colo., have transitioned to largely ethnic markets.

Lamb imports spike for the Easter holidays. In January and February, Australia’s lamb exports to the U.S. were up 28 percent to 10,135 tons (22.34 million lbs.) year-on-year (Australian Department of Agriculture and Water Resources, 3/1/16). Whether or not a significant portion of lamb imports end up in the freezers is immaterial to the market psyche. If domestic processors read the same publicly available reports of higher imports, it might prompt a move to lower domestic prices to compete, thereby depressing the live, slaughter lamb market.

As an industry, we often think in terms of national aggregates. However, there are unique, smaller markets within the broader picture – each with independent market dynamics. We don’t know the import market share in the ethnic market, for example, or the HRI – hotel, restaurant and institutional trade.

Shearing in Full Swing

USDA/AMS reported in early March that spring shearing is in full swing (3/4/16). In early March, 103,000 lbs. of confirmed trades were reported, with much more purchased from growers, core samples taken and prepared for marketing.

U.S. clean wool prices were reported in the Territory States – the West and some California wools. Twenty-two micron brought $3.72 per lb. clean in early March, 1 percent higher from last spring. Twenty-three micron averaged $3.60 per lb., 3 percent higher year-on-year. Twenty-four micron averaged $3.28 per lb., also 1 percent higher. Twenty-six micron brought $2.70 per lb., 9 percent lower year-on-year.

Australian wool prices in early 2016 were higher than a year ago; although somewhat unstable given the recent exchange rate volatility. On March 3, the Australian Eastern market Indicator was Australian 1,258 cents per kg clean, up 16 percent year-on-year. In U.S. dollars the EMI was 919 cents per kg clean, up 8 percent ( AWEX, 3/2/16).

By the second week of March, the EMI in Australian dollar terms had weakened significantly, primarily due to recent strengthening of the Australian currency against the U.S. dollar. The Australian dollar exchange rate hit an eight-month high of 75 cents by March 9, sharply higher than the 70 cents-mark it flirted with for some time.

As a consequence, wool prices in Australian dollars fell to a four-month low, but held relatively stable in U.S. dollars. Market analysts note that the very small decline in U.S. dollar terms suggests that the fundamentals of the market, including strong demand, remain sound (WTiN Wool Market Report 3/14/16).

Exchange rate volatility is part of doing business in the wool industry. While there has been a generally slow improvement in most of the major world economies recently, the expected improvement in retail sales of clothing, which most often results with improving economies, has unfortunately been mostly disappointing during the important Fall/Winter period with only weak growth in major markets (ASI Wool Journal – Poimena).

This, in turn, results in uncertainty for retail orders in coming months. However, wool prices performed better than other commodities during this period and a better result at retail is expected as the world’s economies continue to improve.