- December 2011

- Annual Convention Tours and Schedule Information

- ASI Receives Grant

- Conception to Consumption: Producer Focuses on Diversity

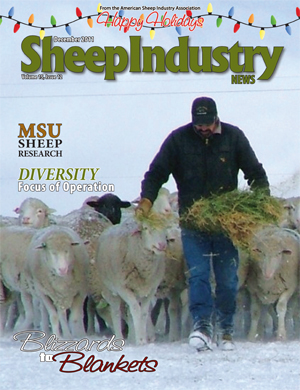

- From Blizzards to Blankets: Mooty Family Revives Historic Minnesota Mill

- Let’s Grow Media Tour Continues in Midwest

- Let’s Grow Topic at Trade Talk

- MSU Receives $743,000 for Sheep Research

- Proper Handling/Management Urged for TX Fine-Wool Sheep

- Research Shows Guard Dogs Relax Sheep

- Vilsack Announces ALB Appointments

Becky Talley

Sheep Industry News Associate Editor

(December 1, 2011) Those who truly have the calling to raise sheep aren’t hard to spot. While many have an extra bounce in their step in times like these when the markets are good, honest-to-goodness shepherds are the ones with a twinkle in their eye and enthusiasm in their voice when they talk sheep, no matter the market prices. They raise sheep because they believe in the animal, their importance in the livestock industry and take a lot of pride in production, genetics and quality.

The American Sheep Industry Association is lucky to be supported by many such sheep producers, and Jared Lloyd of Colorado is one of them.

Lloyd, of Jehovah-Jireh Sheep and Cattle Co., Molina, Colo., is a producer who has steadily worked to expand his flock over several years, all while giving an example of just how diverse his own operation, as well as the entire industry, can be.

Expanding an Interest into a Business

According to Lloyd, his involvement in sheep began “prenatal.” As far as he can trace back, his family ran range sheep in Mesa County in some capacity or another. Many of them began as cattlemen, his grandfather built a cattle empire from two bottle calves, but you might say intervention steered them in a more wooly direction.

“The men on both sides of my family were almost all cattlemen, but they married sheepwomen,” Lloyd relates.

Getting with the sheep program quicker than his predecessors, Lloyd himself was interested in sheep from the beginning. As a home-schooled student he was able to apply his education into sheep projects, which were really the building blocks of the flock he has today.

Like his cattleman grandfather before him, Lloyd has built up a sizeable flock from a few animals, and currently, he raises Shetland and Bluefaced Leicester sheep with a unique focus: to preserve the genetics of each sheep breed but also emphasize the commercial side of production as well.

Lloyd says he stumbled onto the Bluefaced Leicester by accident when he saw a young ram at the Estes Park Wool and Fiber Festival.

“I saw him in the pen and my eyes popped. The loin was long, the rack shape was amazing. I started researching more and in a few years bought some ewes,” he relates.

Today, his flock of Bluefaced Leicesters is bred mainly for seedstock ram production, although the lower end also goes toward meat production, and the Shetlands are primarily sold for meat. Both types of sheep also produce a valuable wool product for Lloyd.

At the base of Lloyd’s breeding program is a focus on genetics. As a youth, he maintained EPDs on his flock and was the first, and still the only, Bluefaced Leicester producer to have his EPDs managed by the National Sheep Improvement Program. Today, he serves as the Bluefaced Leicester Union’s Genetic Taskforce chairman.

As both the Shetlands and Bluefaced Leicesters are fairly uncommon breeds in the United States, those who breed them have not had much outcrossing in their flocks, so Lloyd and a group of breeders have brought in the germplasm of rams from the United Kingdom (UK), which have very distinct genetics. Lloyd himself traveled to the UK to identify rams that maintained the breed characteristics but also emphasized production traits he wants to see in his own ewes.

“I really look for an animal that performs well and is a good milker, an easy keeper, has 200+ percent lamb crop, has good growth and structure and has good hardiness. I want to see a productive ewe that still looks pretty,” he says.

From Farm to Fork and Fashion

A trip to the sale barn was the birth of Lloyd’s direct marketing business. After receiving some disappointing prices for the lamb he was bringing to the auction, Lloyd decided to re-evaluate his sales strategy.

“I just needed to do something different. That day, I decided that everything I sold was going to be sold in white packages,” he says.

Today, he processes most of his Shetland sheep, and the lower-end Bluefaced Leicesters, for the farmers markets and says that racks and chops are the product he moves the most. The Shetland lambs can be processed at about 120 days at the weight of 70 pounds, and according to Lloyd the breed is one of the most efficient converters of grass into meat, milk and wool of the British breeds. It’s a smaller carcass with smaller cuts, but many consumers prefer the size, and Lloyd says the meat has a different flavor profile.

“It’s sort of like comparing the taste of a cherry tomato to a regular tomato,” he says of the taste difference between a Shetland and larger sheep.

Flavor profile, production practices and the locavore food movement are things Lloyd aims to educate his consumers on when they visit his booth. He often provides samples of lamb, and in the past has sold lamb burgers, but no matter the product, always encourages the consumer to notice what they taste.

“I am enthusiastic about consumers tasting the nuances of flavor. I try to educate them when I talk to them and many are wanting the local stuff. There’s a lot to be said from something that is regionally produced,” he says, adding he often provides recipes that he suggests be paired with a locally produced wine to support local agriculture of all types.

He says he is seeing more consumers interested in buying and trying lamb.

“I think it’s been a collective effort on everyone’s part to promote lamb, and its working. Providing a good product has been important,” he says.

In addition to the farmers markets, Lloyd has also been able to get his lamb in with several local restaurants that range from barbecue joints to fine dining and has received endorsements on his product from Michelin rated chefs.

While the lamb business is good, it’s not Lloyd’s only game. Both the Shetlands and Bluefaced Leicesters produce fleeces that are in demand in the hand-crafting world, and Lloyd and his parents, Eric and Penny, have capitalized on that market as well.

For the Lloyd family, the idea has always been to be a fully integrated operation, producing, processing and manufacturing all its own products in order for the company to sustain itself with little to no outside capital.

The wool mill, Sheep Camp Wool Mill, was another step toward that goal. Eric and Penny own the mill, and acquired the machines, like many mills, from others who have gone out of business. They buy a majority of Jared’s wool clip and produce yarns (natural, dyed and hand painted), felted goods and scarves, to name a few products, which are sold at farmers markets and a local textile store.

According to Eric, they are processing about 1,200-1,800 pounds of raw wool a year for the woolen line.

“It’s all family. He’s producing and we are processing,” says Eric. “We decided to do this without going into debt, and so far, it’s mostly paying for itself.”

Producing Seedstock and Taking it Commercial

Lloyd is planning on increasing the commercial side of his operation shortly, while maintaining the integrity of his Bluefaced Leicester and Shetland lines.

On the commercial side, he hopes to add 500 fine-wool ewes to the operation, of which the top 100 will be bred to a super-fine wool ram and the rest crossed to a Bluefaced Leicester ram.

“With the price of wool, I think it’s a good way to go, and the Bluefaced Leicester/fine wool cross makes a really nice animal. You lose about two microns in the cross, but gain in staple length and animal size,” he says, adding that he hopes to be able to contract his lambs with buyers from this venture.

He still plans to keep the Shetlands for the farmers markets and artisan lamb product market, and is aiming to expand into the resort restaurant, retail and direct markets in the closely located ski towns like Vail. He aims to increase his Bluefaced Leicester flock to 200 ewes, so he can produce enough ram lambs to cover his commercial ewes as well as to sell for seedstock.

As Lloyd has a strong interest in genetics, next fall he plans to put together a grass-finishing genetics company, in which he will be importing mostly Shetland genetics and a few other British breeds from the UK that do well in a grazing system.

“I am emphasizing productive lines and am looking for performance on grass management systems. Mostly I will be looking at old hill stock and old genetic lines,” he says.

As growth for his operation requires land, something that is scarce in his area, Lloyd is also pursuing targeted grazing contracts with some of the oil fields that are prevalent in that part of Colorado. It is just another example of the diversity of the Lloyds’ operation, as they continue to build and grow their sheep and mill business.

“We are making this as sustainable as possible,” says Lloyd. “Little by little, we are building it.”