To View the September 2021 Digital Issue — Click Here

Relationships are the Backbone of our Industry

Susan Shultz, ASI President

If I could pick a theme for our recent ASI summer executive board meeting it would be building relationships to achieve common goals.

Building relationships is defined here as open communication, trust building and perseverance. The keys to achieving common goals – especially in an industry as diverse as our sheep industry – is developing trusting relationships and understanding the diverse issues facing each of us. Our recent summer ASI Executive Board meeting worked at accomplishing both.

The last time our executive board had an in-person meeting was March of 2020 in Washington, D.C. That was when we were one of the last commodity groups to visit our representatives and senators on the Hill before the pandemic shuttered their offices. Being together again this summer in South Dakota was a first step for the new board members to interact with those who have served longer. We engaged in honest conversations, which is a prerequisite in building trust.

Our summer meeting was packed with reports of ongoing projects and new initiatives. Topics included legislative priorities, targeted grazing, electronic identification tag adoption, the new American Wool Assurance Program, the Secure Sheep and Wool Supply Plan and much more. In conducting the official business of our association, we recommended the adoption of the Wool Trust budget and the Fund II budget for 2022. All eight regional directors, the officer team and the National Lamb Feeders Association representative participated in reviewing our mission and vision statements and spent time listening to each other’s goals and concerns for our industry. Active listening is certainly one important element in developing two-way communication, which helps to build relationships.

I think most would agree that of all the producers of animal proteins, the sheep industry could be the most diverse. We have intensive and extensive production systems, diverse breeds, diverse markets and diverse producers. But what unites us are our common goals. Our current board reflects those diversities and makes for invigorating conversations on how best we as a board can move our industry forward in order to maintain our focus on our mission and vision.

Special guests at our meeting included Gwen Kitzan and Peter John Camino – chair and vice-chair, respectively, of the American Lamb Board – who delivered an update on the positive activities of ALB. Zach Ducheneaux – the new administrator of the Farm Service Agency – was also on hand. Administrator Ducheneaux led us in an open and thoughtful discussion on present day FSA programs and their implementation.

Rounding out our day of building relationships was a reception with the South Dakota Sheep Growers Association. Not only did we catch up with old friends, but we also gained a better understanding of their needs that ASI can help address. Meeting the South Dakota State University sheep educators – Dr. Kelly Froehlich, Jaelyn Quintana and Heidi Carroll – was a delight.

On day two, we had the special opportunity to tour the ranches of two longtime sheep ranching families: the Pilster and the Nuckolls families. We were able to learn firsthand about the issues that Western ranchers are facing in the midst of a severe drought. We also listened to the optimism of raising sheep and their dreams for the future of their ranches. Both families reminded me how working at building relationships in our industry through numerous years of dedication and involvement has benefited us all. We are indebted for their continuous support.

Constantly working on building trusting relationships within our industry through listening and learning about the needs of each other is key to our success.

My best.

JULIE STEPANEK SHIFLETT, PH.D.

Juniper Economic Consulting

There are too many headlines to choose from – Slaughter Lamb Prices Topped Records; Feeders Surpassed $300 per Cwt.; July’s Cutout Beat $6 per Lb.; Record Low Summer Inventories; or Pasture and Range Conditions Worst on Record. The American lamb industry is in uncharted territory which begs the million-dollar question, is this a bubble or the start of a long-term trend?

If we are witnessing a bubble, will this fast surge in prices lead to a crash? If the current price acceleration is a bubble, then that means the recent exuberant market behavior isn’t tied to lambs’ intrinsic value, that is, price doesn’t align with supply and demand. Market fundamentals suggest otherwise, this is not a bubble. There might be some price softening in months to come, but indicators suggest that the market might stabilize at historically high price levels.

Domestic lamb prices are high because supply is tight and demand is strong. In 2020, the shutdown of the foodservice sector, rise in mainstream retail sales and strengthening ethnic lamb sales prompted increased demand. Brian Phelan, director of procurement at Superior Farms, commented at the recent Colorado Wool Growers Association Convention that the Muslim Eid ul-Fitr – festival of fast breaking – coincided with the largest 2020 weekly harvest. In 2021, the foodservice sector slowly came back online, retail is staying strong, and consumer spending of pent-up demand and stimulus checks is supporting current high price levels.

Domestic supplies are tight, inventory is down and packers are bidding up lambs to secure fall supplies. By the end of July, live weights in federally inspected harvest dropped to 120 lbs. – compared to closer to a 138-lb. average in 2014 to 2018 – suggesting packers are scurrying to get lambs harvested to fulfill contracts of light-weight lambs in mainstream and ethnic markets. The wild card remains imports. Lamb imports were lower year-on-year in the first quarter, but injecting more imports into the market can lead to a softening of domestic live lamb prices. Domestic lamb support will hinge upon consumers choosing American lamb.

There is risk in any market forecast. Some packers report that consumers are beginning to push back on the higher prices and that they are losing money for some lambs at current prices. The mainstream and ethnic markets are merging, which further complicates market forecasts. In 2022, live lambs will likely stay above $2 per lb., but the meat market has to stay high, and feed costs manageable.

The American Lamb Board has implemented unique marketing programs to support the current demand momentum. In 2020, ALB and Texas grocery chain H-E-B partnered to boost American lamb sales. ALB also joined forces with Taziki’s Mediterranean Cafe in the first-ever American lamb chain restaurant promotion.

Slaughter Lamb Prices Hold Above $2 per Lb.

Once again, the sheep industry broke records in July. Live, negotiated slaughter lamb prices averaged $262.74 per cwt., 12 percent higher monthly and the third consecutive month of gains over $2 per lb. The last time the industry saw prices surpass $2 per lb. was 10 years ago, mid-July 2011.

Wooled and shorn lambs, 100 to 150 lbs., brought $210.25 per cwt. at the San Angelo, Texas, auction, up 5 percent monthly and 55 percent higher from a year ago. Prices at the Sioux Falls. S.D., auction averaged $279.13 per cwt., up 6 percent in July and up 113 percent year-on-year.

The pelt market continued to improve into July as witnessed by growing interest from China. Pelt prices remain unreported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Marketing Service, for there are not enough market participants to protect confidentiality.

Feeders Topped $3 per Lb. in Online Auction

On average, 60 to 90 lb. feeder lambs weakened 2 percent in July to land at $256.40 per cwt., up 49 percent year-on-year. Prices gained at the San Angelo auction in July, but weakened in the Fort Collins, Colo., and Sioux Falls auctions. Prices averaged $264.14 per cwt. in San Angelo, $242.63 per cwt. in Fort Collins, and $262.43 per cwt. in Sioux Falls. Fort Collins saw the most pronounced rebound from last year, up 61 percent from last July.

More than 12,000 feeder lambs traded in the Western Video Sheep Video/Internet Auction, Cottonwood, Calif. Prices averaged $272.50 to $290 per cwt. for 85 to 105 lbs. from Western states and for August to November delivery. Nine hundred head traded out of the North Central United States at $282.50 per cwt. for 102 lbs.

Mor than 13,000 feeder lambs traded at the July Northern Livestock Sheep Video/Internet Auction, Billings, Mont. Lambs out of the North Central United States saw $294.03 to $303 per cwt. for 80 to 105 lbs. and August to November delivery. Lambs from the West averaged $305 per cwt. for 90-lb. lambs and October delivery. The USDA/AMS explained in late July that “the best demand (at the Montana sale) was for heavy-weight lambs which will be delivered later in the year as buyers factor in feed cost into purchases.”

Pressure on Western Fall Pastures

Western pasture and range conditions are the worst on record, meaning a lot less fall pasture available for Easter lambs. In July, the percent of range and pastures that ranked very poor and poor in the West by USDA was 33 percent of total pastures, up 1 percent from June and up 17 percent from a year ago.

Nearly one-third of the nation’s ewes call the West home and face challenging fall feeding conditions. The region has seen dry pasture/range conditions in the past, including the fall of 2002, fall of 2007, fall of 2012 and fall of 2018, however, this is the first-time dry conditions this severe have been recorded during the summer months.

Wholesale Lamb Surpasses $6 per Lb.

The lamb cutout averaged $620.31 per cwt. in July, up 8 percent monthly and up 50 percent year-on-year. In July, primals were 44 to 60 percent higher than a year ago. The 8-rib rack, medium, averaged $1,315.49 per cwt., up 9 percent monthly; the loin, trimmed 4×4, averaged $922.83 per cwt., up 9 percent monthly; the leg, trotter-off saw $562.08 per cwt., up 6 percent monthly; and the shoulder, square-cut, averaged $477.65 per cwt., up 9 percent from June.

Ground lamb averaged $804.71 per cwt., up 7 percent monthly and up 46 percent year-on-year.

Domestic Supplies Tight

In the first 29 weeks of the year through mid-July, estimated federally inspected lamb harvest totaled 1 million head, up 1 percent year-on-year and down 5 percent from the same period in 2019. Estimated lamb production was 49.1 million lbs., down 2 percent year-on-year and down 10 percent from the same period in 2019. More lambs are being harvested but at lighter weights than a year ago. Phelan said many customers want light lambs, and don’t care if they are wooled or hair lambs. Phelan added that hair sheep work well to fulfill light-lamb contracts, but Superior Farms harvests some light-weight wooled lambs, as well.

Feedlot inventories remain relatively low in August, but numbers are likely to grow into the fall. Colorado feedlot inventory at the beginning of August was 59,639 head, 30 percent higher year-on-year and 9 percent lower than August’s five-year average. Phelan noted recently that reduced Colorado feedlot numbers in 2020 and 2021 could directly reflect the diversion of lambs to the ethnic trade.

The industry might find that fulfilling summer demand meant harvesting lambs that otherwise would not be harvested until the fall, and thus the fall will face an extreme short supply.

In early August, the Livestock Marketing Information Center released its lamb and mutton supply and utilization forecasts for the year. Total production in 2021 could be 141 million lbs., down 2 percent for the year; imports could be down 7 percent to 282 million lbs., exports could double to 7 million lbs., and ending stocks might be down 30 percent to 98 million lbs. Total lamb and mutton available for consumption in 2021 is expected to be down 8 percent in 2021 to 417 million lbs.

Lamb Imports Rebound

After slower lamb imports in the first few months of 2021, June imports rebounded sharply from a year ago, up nearly 150 percent. By June, Australian imports totaled 21.7 million lbs., up 53 percent monthly; New Zealand imports were up 31 percent to 7 million lbs. with total imports up 45 percent to 29.4 million lbs.

In the first-half of 2021, lamb imports were up 13 percent year-on-year to 121.2 million lbs.; Australian imports were up 8 percent to 87.1 million lbs., and New Zealand imports were up 28 percent to 31.9 million lbs.

In the first-half of 2021, lamb exports were down 12 percent year-to-year at 236,000 lbs. and mutton exports were down 80 percent year-on-year to 1.3 million lbs.

Australian Wool Breaks for Recess on a High Note

In the last sale before its three-week recess, the Australian wool market saw Australian $1,428 cents per kg clean, up 26 percent year-on-year. In U.S. dollars, the Eastern Market Indicator averaged $4.83 per lb. clean, up 36 percent year-on-year. The Australian market performed well, with a surge in buyer activity before the summer recess.

Coarser wools have continued to struggle worldwide. Crossbred wools – 25 to 32 micron – gained only 0.25 percent in June and July from last summer, compared to a 26 percent gain across all wools. Australian Wool Innovation Ltd. reported in mid-July, that the EMI saw “some very welcome and high percentage gains on crossbred wool types being the most significant.”

The American sheep industry is seeing a structural change. Hair sheep numbers are increasing, but wool breeds are also expanding in pockets of growth in the Midwest and East, and that can change the wool market landscape. In 2017 to 2021, ewe inventory expanded in the Midwest, Great Lakes and Northeast. Ewe numbers stabilized in the Mid-Atlantic states. By contrast, Western states saw ewe numbers contract by 8 percent in five years. Texas ewe inventory was up by

1 percent in this time – primarily due to gains in hair sheep.

As wool breeds expand in the East – from Merino to Suffolk to Romney, but mostly coarser wools – wool infrastructure from local wool pools to small- and mid-sized wool mills expands. A wool pool serves to collect growers’ wool in order to accumulate sufficient volume of like wools for improved marketing. ASI reports 54 wool pools across the United States, about 20 of which lie east of the Mississippi River.

About one-third of the American wool clip is considered coarse wool. The United States produces about 1 percent of 18.5 micron and finer wools, 66 percent of 18.6 to 24.5 wools, 31 percent of 24.6 to 32.5 wools, and 2 percent of 32.6 and broader wools. Fine crossbred wool – 25 to 28 micron – can be used for men’s and women’s outerwear, knitwear and socks. Medium crossbred – 29 to 32 micron – can be used for hand-knitted yarn. Coarse wool – about 32 micron and coarser – is used primarily for interior textiles, such as carpets, blankets, upholstery and yarn. Coarse wool has also been used in bedding material, insulation and even as a composite to make surfboards.

The primary culprit in lower coarse wool prices is lower demand due to the substitutes of cheaper synthetic fabrics in floor coverings. Finer wool blends well with synthetic fibers, which helps manufactures producer “greener” apparel. However, coarser wools have struggled to find a niche in today’s environmentally-conscious products.

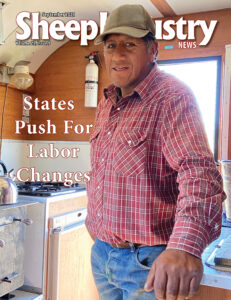

Planned wage increases for H-2A herders in California and Colorado in 2022 will certainly be felt by producers in those states. But they might simply be the first dominoes to fall in an economically challenging game for sheep producers throughout the West.

The most recent labor war involving sheepherders has left producers in each of those states contemplating the future of their farms and ranches. All isn’t lost just yet, however. California legislators appear open to a work-around option that would keep the sheep industry alive in the Golden State, while Colorado’s wage increase and other unreasonable regulations are headed into the state’s rulemaking process.

Regardless, producers who use H-2A herders are facing yet another challenge after major changes to the federal program in 2015 that saw a significant bump in wages mandated by the United States government. California has traditionally been the starting point for labor changes in the program and generally holds producers to a higher minimum wage than the federal requirements.

“That’s been a concern of ours all along,” said California producer Ryan Indart. “So much of what happens in other states is riding on what happens here in California. Andrée (Soares) and I are both on the board of Western Range, and we have friends scattered through other Western states who are watching this like a hawk. And they should be.”

For that reason, Indart and Soares encouraged other state sheep associations to setup their own legal defense fund – similar to ASI’s Guard Dog Program – as soon as possible if they don’t already have one in place. The California Wool Growers Association started its fund just a few years back – when Indart served as president – and it has played an essential role in the state’s wage battle.

“This battle is expensive, and we don’t know how long we’re in it for,” Soares said. “I think we’ve been effective in our work. Plan ahead and have a war chest prepared for when you need to fight this battle yourselves. We’ve made a lot of progress, but we can’t just snap our fingers and make everything go back to normal. It takes time and a lot of work.”

CALIFORNIA

In 2016, California passed an overtime law for agricultural workers – AB1066 – that went into effect in 2019 for employers with 26 or more employees. The law will be extended to those with 25 or fewer employees in January, and will take a drastic toll on sheep producers in the state as it requires pay for a 168-hour work week as the law considers herders to be on call 24 hours a day. CWGA representatives have proposed a 48-hour work week in line with federal H-2A guidelines.

“We’re not abandoning that effort,” Indart said. “As the politics of California keep evolving, we’re still hopeful that the governor will direct his labor agency to adopt this 48-hour solution. He has the ability to do that.”

“We’ve been told – not by the governor’s office, but by the legislature – there isn’t a path forward for that option. To that end, we’re continuing to get counties to adopt resolutions in support of that effort.”

In the meantime, a temporary solution might be available for sheep producers in the state.

“In California, they are bathing in money right now,” Indart said. “So, money is the solution to everything. There is money in the budget to attach a trailer bill so that we could get this increase covered for producers by the state.”

The office of Calfornia Senate President Pro Tempore Toni Atkins asked CWGA to provide information on the additional labor costs to producers. In 2022, that cost is estimated at $4.6 million and would rise to as much as $8.3 million by 2025.

Through the trailer bill, the state would compensate any California sheep producers who employ H-2A herders for these additional costs.

“We can’t say no to an open door,” Indart said of the proposal. “We don’t see this as a viable, long-term option, so we’re working both tracks. The 48-hour option is our long-term, permanent fix. The trailer bill option is a solution that just came up a month ago. We’ve provided the senator’s office with the data they need to put together a payment scenario.”

Adding to the pressure to keep sheep producers in the state in business is California’s reliance on targeted grazing to mitigate fire hazards. In yet another hot, dry summer in California, the important role sheep and goats play in protecting urban and suburban communities has not gone unnoticed.

“And we need even more herders per head to operate than a traditional sheep producer,” said Soares, who runs targeted grazer Star Creek Land Stewards. “One concern is that this solution does not offer any protection for producers from other states from being impacted. Their states might follow California’s overtime law, but not have the additional money to throw at it. If we get the 48-hour solution, we feel like that offers more protection to the rest of the states.”

“We don’t want the industry to get the idea that this battle is over,” Indart added. “We are continuing to fight and we aren’t going to give up until we get the solution that we need, which is the 48-hour work week or something similar. Until then, we might have to work with this Band-Aid solution and ride things out until we can get a legislative solution.”

COLORADO

Also set to go into effect in 2022 is Colorado SB87, which would increase herder pay from $1,727 a month to $2,060 a month. But there are other regulations included in the bill that are just as troubling for producers as the pay increase.

The bill also requires that herders be taken into town at least once every three weeks, and provides language for “key provider access” that creates a boatload of concerns about access to private property.

“Advocates who pushed for these changes admitted they were following the changes in California law,” said Colorado Wool Growers Association member Steve Raftopoulos. It’s very disheartening to have city people forcing rules and regulations on rural Colorado without any real understanding of what it takes to provide food and fiber for the state.”

Provisions of the bill are set for the state’s rulemaking process, which was scheduled to begin in mid-August and run through the fall. That means producers will have just a short amount of time to adjust to new regulations before they take effect in early 2022.

“What they did with the pay increase was take the minimum wage in Colorado and multiply it times 48.33 hours – the hours the federal government determined are worked by sheepherders,” said Raftopoulos. “And that is the wage we’re going to pay. But we also pay room and board. If you look at what a sheepherder is making, it’s way more than anyone else who is working for minimum wage in Colorado. If someone is working for that wage in town, they still have to provide their own home and buy their own groceries.”

The requirement to take herders to town will be especially onerous for producers. Sheepherders spend the summer in remote areas. The time required to get to them, take them to town and return them to their camps could well become a full-time job for producers. Not to mention, many of the herders have no interest in going to town in the first place.

“If we have a herder who needs to go to town, we take a look at what’s going on and find a time when it works for our operation,” Raftopoulos said. “But we’re also willing to do their banking and shopping for them, and most of them are fine with that. If they want to do it themselves, they’ve always had that option. But if we’re mandated to get them to town once every three weeks, that makes it very difficult. That means we have to hire an additional man because we can’t leave those sheep alone.

“We’re going to try through the rulemaking process to address that issue. What we hope we can do for the industry is to give workers the right to waive that requirement. If they don’t want to come to town, they shouldn’t have to.”

Based in western Nebraska, Aaron Fintel runs an old-school, modern-day sheep farm in the free moments he finds between selling John Deere tractors and attending his two sons’ sporting events and school activities.

Open Skies Farms is old-school in the fact that Aaron bases many of his management decisions more on what feels right in the moment than on hard data. But like a modern-day producer, he’s also open to new ideas. What has evolved is an ever-changing operation that can take on a bit of a Jekyll-and-Hyde feel, and one that many small-scale sheep producers can probably relate to.

“If it doesn’t work, then it’s done,” he says with little remorse. “That’s just my nature. I have a natural way about me to try and reinvent the wheel. There is not a structured management practice in place, so we just kind of go with whatever fits and feels right for us.”

His sons, Jacob and Jonathan, and his fiancée, Brandi, are accustomed to the barrage of new ideas that he floats on a regular basis. Not a single one of the three is surprised when he mentions yet another concept he might like to try.

And while the method to his madness might be difficult to identify at times, the feedlot nature of the operation drives Aaron on a daily basis.

“The biggest thing I’m always searching for is the silver bullet on the feeding side,” he admits. “It’s not necessarily the raising of the lambs, but the ewe feed and the cost of it. I’m always trying to manage that and figure it out.

“We’ve tried different stuff. We’ve tried wheat hay and bean hay. I would love to feed that bean hay all year, every year. It was super cheap, because obviously that’s not the point of pinto beans. Body condition on the sheep was amazing all year. It made no difference whether we were nursing or flushing or if it was 100 degrees in July. The sheep just looked beautiful all year long. They were pre-harvested beans that still had pods in there, so we could crank back on the corn because they were getting so much protein from the beans.”

Never heard of feeding bean hay to sheep? It’s not generally an option for Aaron’s operation either, but an August hail storm in 2019 took out much of the local crop as the beans were nearly ready for harvest.

“A friend of ours had two half circles of pinto beans that they had swapped and bailed,” Aaron recalls. “As you can imagine on a drylot operation, we’re always concerned about feed costs. So, we’re very open-minded. He brought over those pinto bales and we dropped it in the feeder.

“We were really happy with that. A lot of studies will tell you to be careful about feeding dry beans to sheep, but they were mature beans, about ready for harvest. I figured the sheep would get a lot of protein, but also a lot of roughage that would help the rumen. And, it worked. The farmers in this area are really hoping that’s never an option for me again.”

The ewes get a steady diet of grass hay and corn nearly every day, with other options rotating on and off the menu depending on the time of year and what’s available (like the bean hay).

“We will have gone in two years from buying every single thing they eat to selling hay this winter if everything goes well,” Aaron says. “That’s a huge flip for us.”

Katahdins, Dorpers Dominate flock

Changes in the operation aren’t limited to feeding, however. Breeding decisions have been a constant source of experimentation at the farm. Katahdins and Dorpers (and their crossbreeds) make up the majority of the flock these days. But there was a Polypay experiment and thoughts of Romanovs keep dancing in Aaron’s head. And his dad – there’s a lot of interaction between the two operations – dabbled in Finnsheep at one point.

But breeding decisions in recent years have mostly revolved around the Katahdins and Dorpers.

“The biggest reason we do lots of crosses is for raising our own ewe lambs,” Aaron says. “It’s not about meat production. We decide what we want for ewe lambs around here and that’s how we decide what to cross.

“Mostly what we’ve done is throw Dorper rams on Katahdin ewes and Katahdin rams on Dorper ewes, so it’s a 50-50 cross both ways. We take all of those ewe lambs and then we can pick what we want to do that year. We breed Dorper if we’re going to sell everybody for meat. We breed Katahdin if we want to keep back the ewe lambs.”

In general, Aaron is a fan of the Dorpers. But they come with some issues he could live without: they’re shaggy, have hoof issues and don’t birth multiples as often as the Katahdins.

“We’ve been heavy Dorper and now we’re heavy Katahdin,” he added. “The ewes require far less maintenance than the Dorper ewes and offer multiple births. Katahdins are the longhorns of sheep. They can live through anything and they can eat anything. They would rather run over you than let you get by their lambs, but they grow as slow as molasses. They’re awful feeder sheep, so that’s where the Dorper influence is important to us.”

As previously mentioned, time is in even shorter supply than feed at Open Skies Farms. The adults have full-time jobs. The kids have school and seemingly unlimited activities afterward, so the sheep have to be somewhat self-sufficient.

“Lambing is never going to be a baby-sitting project around here,” Aaron says. “In a perfect world, everyone has twins, we wean twins and sell twins. But that doesn’t always happen. We aren’t setup for bottle lambs around here. We might be the only drylot in America that doesn’t have bottle lambs.”

Time was also a factor when Aaron decided to step down as president of the Nebraska Sheep and Goat Producers Association earlier this year. He began serving on the association’s board in 2017.

“I always wanted to be on the board because I’m so passionate about the sheep industry,” Aaron says. “But, I recently stepped down as president due to time constraints. I know they’re in good hands.”

Without that role with the state association on his plate, Aaron has a few more minutes each day to develop the next big idea for Open Skies Farms.

Sheep have been trailing through the Wood River Valley of Idaho for more than a century. For the past 25 years, sheepherding, history, culture and food have been the focus of the annual Trailing of the Sheep Festival held each fall in the Sun Valley area.

Trailing of the Sheep was recognized as one of the Top Ten Fall Festivals in the World by msn.com.

For its 25th anniversary – Oct. 6-10 – the Trailing of the Sheep Festival is planning a special celebration with new programs and events, including the unveiling and dedication of The Good Shepherd Monument. The legacy tribute includes eleven life-sized bronze sculptures featuring eight sheep, a sheepherder, horse and dog to be installed in Hailey, Idaho.

The festival honors the more than 150 year annual tradition of moving sheep from high mountain summer pastures down through the valley to traditional winter grazing and lambing areas in the south. This annual migration is living history and the focus of a unique and authentic festival that celebrates the people, arts, cultures and traditions of sheep ranching in Idaho and the West.

The five-day festival includes nonstop activities in multiple venues – history, folk arts, a Sheep Folklife Fair, lamb culinary offerings, a Wool Festival with classes and workshops, music, dance, storytelling, championship Sheepdog Trials and the always entertaining Big Sheep Parade with 1,500 sheep hoofing it down Main Street in Ketchum, Idaho.

2021 Festival Highlights include:

• The Big Sheep Parade in Ketchum;

• Championship Sheepdog Trials with 100 talented border collies competing for prizes;

• Sheep Folklife Fair featuring Basque, Scottish and Peruvian dancers and musicians, sheep shearing, folk, fiber and traditional artists, children’s activities and more;

• The Sheep Tales Gathering will present celebrated author and essayist Gretel Ehrlich to share her stories of losing authenticity to land and place, the sanctity of the land and the earth, and her love of the land, based on her acclaimed collection of essays on rural life in Wyoming titled, The Solace of Open Spaces.

• 25th Anniversary Celebration Peruvian Ballet Folklorica, performed by the Utah Hispanic Dance Alliance and Chaskis Peruvian Musicians, and focusing on Andean music and dance.

• Culinary Events with lamb tastings, Lamb Fest at the Folklife Fair, lamb cooking classes and farm-to-table lamb dinners;

• Wool Fest with classes and workshops;

• Hikes and Histories featuring Idaho’s sheep ranchers and renowned storytellers;

• Happy Trails Closing Party with live music by Cindy & Gary Braun and Gator Nation in partnership with the Sun Valley Jazz and Music Festival.

In celebration of its 25th year anniversary, the festival is presenting its new Trailing of the Sheep Festival Cookbook that features authentic recipes from Idaho ranch families and festival friends for dishes such as sheepherder bread, Basque rice, Turkish lamb kabobs, tagine of lamb and more. The cookbook will be available at all locations selling festival merchandise.

The Trailing of the Sheep Festival quilt raffle is for a special 25th anniversary quilt, made up of 15 individually created sheep related quilt squares and designed to be a twin-sized bed topper or a wall hanging. Raffle tickets will be available for sale at the festival, with the drawing for the winner held at the Happy Trails Closing Party on Oct. 10.

The Trailing of the Sheep Festival began in 1996 when local ranchers John and Diane Peavey of the Flat Top Sheep Company invited the public to trail with their sheep through the backstreets of Ketchum on a fall morning to learn about the history of sheepherding in the valley. This was in response to the rapid loss of farms and ranches, growth in Idaho and the West, and arrival of new residents who had little knowledge of the sheep industry and its history.

The following year, the Peavey’s met with the local Sun Valley/Ketchum Chamber and Visitor Bureau and together they created a multi-day event to showcase the area’s unique cultural heritage and invite visitors to come during the beautiful fall season to experience an authentic slice of the American West.

For information, visit www.trailingofthesheep.org.

The Sheep Heritage Foundation – a division of ASI – has awarded its 2021 scholarship to Brian Arisman of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. The $3,000 award will be used to support his master’s degree work in animal breeding and genetics.

Originally from Delaware, Arisman earned a bachelor’s degree in agricultural and medical biotechnology from the University of Kentucky in May of 2020. He was accepted into the graduate program at UNL’s Department of Animal Sciences in January of 2020. Arisman previously served as the Miller Animal Science Intern at the University of Missouri, as a student researcher at Kentucky and as an undergraduate research scholar at the University of Delaware before taking on a research assistantship position at UNL.

As a student still working on his master’s degree, Arisman said he was surprised to win a scholarship that has often gone to Ph.D. candidates.

“I’ve still got at least a year on my masters, but I plan to pursue my Ph.D., as well,” he said. “I’m thankful for the opportunity to receive this scholarship at this point in my career. I want to continue to work with sheep and small ruminants.”

While much of his early sheep experience came from showing lambs in 4-H, Arisman said his favorite part was always selecting the lambs that he wanted to use. That led to a desire to study genetics in college.

He’s worked on research projects involving a variety of species, but Arisman’s current research looks at gastrointestinal nematode parasites in sheep. Infection with GIN parasites can result in weight loss, decreased appetite and even death.

“In my current study, genetic resistance and resilience to GIN infection will be delineated using fecal egg counts and FAMACHA scores,” he wrote in his scholarship application. “Resistance is the ability of the host animal to exert control over the parasite, while resilience is the productivity of an animal in the face of infection. Phenotypic and genetic (genomic) relationships among FEC, FAMACHA scores and body weights will be estimated, and used to identify resilient and resistant individuals.

“Additionally, tolerance to GIN infection – which is the change in performance with respect to changes in pathogen load – will be considered. At least initially, tolerance will be evaluated at a sire level by regressing mean body weights on mean FEC or FAMACHA scores of offspring with different pathogen burdens; the slope will define genetic sensitivities to pathogenesis. Beyond pathogen load alone, sensitivities to a broader set of environmental challenges also will be explored. Flocks will be clustered into ecoregions defined by climatic variables. That clustering will be complemented by a producer survey to identify differences in management practices across flocks related to parasite exposure-levels.

“The outcome of this research will be genetic and genomic tools to more reliably select sheep to cope with GIN infection across varying environmental and management conditions.”

At Nebraska-Lincoln, Arisman is working with sheep industry veteran Dr. Ron Lewis, who recommended his student for the scholarship.

“Since arriving in Nebraska, Brian already has helped a local 4-H club provide training in handling and managing small ruminants,” Lewis wrote in his recommendation letter. “His long-term ambition is as an extension specialist in small ruminant and fiber bearing species aiding new or current producers to establish a breeding plan for their operation.

“Beyond his sheep industry experience and academic achievements, I also was keen to recruit Brian because of his past research accomplishments. His internship at the University of Missouri introduced him to genomic analyses. He also studied approaches for defining distinct climatic ecoregions across the U.S. Brian’s work at the University of Delaware familiarized him with the measure and use of fecal egg counts to monitor internal parasitism. Those experiences neatly mesh with his current research at UNL.”

Clay Elliott, Ph.D.

Purina Animal Nutrition

Breeding seasons and reproductive management strategies differ around the country.

No matter your breeding program, all flocks want more ewes bred early and more sets of healthy twins born. Here are three commonly asked questions regarding reproduction with answers that can help you meet flock breeding goals.

How does flushing ewes benefit flocks, and how do you do it?

Flushing ewes with improved nutrition helps optimize conception rates and percent lamb crop. When you effectively flush ewes, the results can turn into more profitability.

An advantage of flushing ewes with increased nutrition is the improvement in body condition. Ewes should be at a minimum body condition score of 2.5 before breeding and at a maximum BCS of 4. Being at an ideal BCS helps optimize reproduction and overall performance. When ewes are too thin, they might be more susceptible to health issues and can take longer to breed. When ewes are over-conditioned, they typically take longer to breed and are less efficient at converting nutrition.

Evaluate your current nutrition program through condition scores. If BCS needs to improve, add more fat and protein at least three weeks before turning out rams. For commercial flocks – particularly those on range – it might be difficult to feed ewes in a bunk, but tubs and blocks can help them realize the benefits of flushing. Tubs with 25 percent protein and 10 percent fat will work well in this situation.

Mineral is a vital part of flushing to optimize reproductive outcomes. Maintain mineral intake throughout the lead-up to breeding and afterward. A highly palatable, weatherized mineral helps ensure intake will keep up with the nutrient needs of ewes. Ideally, provide mineral year-round, not just at breeding, so ewes never need to catch up.

How should rams be managed before and during the breeding season?

Conducting breeding soundness exams on rams before turnout will determine the fertility of each ram and establish whether they have soundness issues, such as lameness. After all, if a ram’s sperm isn’t fertile or he can’t keep up with the flock, he won’t be able to get the job done.

Similar to ewes, aim for rams to have a BCS of 3 to 4. Extra condition is beneficial as rams will lose body condition during the breeding season. However, if they get above a BCS 4, you might see diminishing returns as rams can become lazy and not stay with the flock.

During the breeding season, monitor rams to help ensure they are staying healthy. Hoof and leg issues are the most common problem rams have because they are working hard to breed each ewe.

How long should the breeding season last?

A rule of thumb is to leave rams out on ewes for 60 days. A 60-day breeding season allows ewes to go through approximately three estrus cycles.

Breeding in a tight, 60-day window benefits the performance of flocks by putting together a more uniform lamb crop. Additionally, the earlier ewes breed, the more overall pounds the flock will wean. Consider using a teaser ram or controlled internal drug release devices to help get ewes synchronized and improve conception at the start of breeding.

The goal is for ewes to conceive on their first service, but that doesn’t always happen. It’s important to focus on nutrition before and during the breeding season, along with ensuring rams are fertile so breeding can happen at the start of the season.

Visit purinamills.com/sheep-feed to learn more. Clay Elliott, Ph.D., is a small ruminant technical specialist with Purina Animal Nutrition. Contact him at [email protected].

EMMETT KEITH INSKEEP, 1938-2021

Emmett Keith Inskeep, a native West Virginian who grew up on a diversified livestock farm in Medley, W.V., died on Aug. 5, 2021. Born Jan. 11, 1938, at 12 Myrtle Ave. in Petersburg, W.V., he was the son of the late Emmett VanMeter and June Marie Clower Inskeep.

Keith grew up on the family farms at Medley and Martin, helping his mother – a revered elementary teacher – and grandmother with gardening and food processing and his father and uncle, William Inskeep, with their multiple farm enterprises. He was especially involved in planting and cultivating corn, harvesting hay and grain crops, milking cows and all aspects of raising chickens and turkeys. He was active in 4-H, where he learned to shear sheep and became a West Virginia 4-H All Star. He attended the one-room school in Medley for five years and earned the Golden Horseshoe in West Virginia History in eighth grade at Petersburg High School, where he was salutatorian of the class of 1955.

Keith completed an associates degree in agriculture at Potomac State College (1957) and a bachelors in dairy science at West Virginia University (1959). He earned a masters in genetics (1960) and a Ph.D. in endocrinology (1964) at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Keith returned to WVU as an assistant professor in the College of Agriculture and Forestry in August of 1964 and spent his entire teaching and research career as an animal husbandman and reproductive physiologist at WVU. He was an original member of the interdisciplinary Faculty of Reproductive Physiology formed in 1965 and served as its volunteer chair until his retirement as professor emeritus in December of 2016.

During his tenure, Keith developed new courses in endocrinology of reproduction and current literature in animal science and taught a variety of courses in animal production and management. He did research with cattle and sheep, much of it at WVU’s Reedsville and Wardensville farms and in cooperation with producers on their farms. He guided graduate students from throughout the United States and from several foreign countries. Their successes and research papers gave him an international reputation in reproductive physiology and management of ruminant livestock. He received the L. E. Casida Award for Excellence in Graduate Education from the American Society of Animal Science in 1999.

Keith was a co-author of and participated in the Allegheny Highlands Project in the 1970s, promoting improvements in ruminant production systems in nine West Virginia counties. From 1975 to the early 1990s, he participated in an exchange program with Spain and traveled to speak and consult in several other countries. He received the WVU Benedum Award for Distinguished Research in Biomedical Sciences in 1996 and a USDA Superior Performance in Research Award in 1999. From 1998 through 2015, he participated in the Small Ruminant Development Project that stopped the decline in sheep numbers in West Virginia. He guided research that led to FDA approval of systems to deliver hormones to induce out-of-season breeding in sheep. His research had global impact and is widely used today.

He was named a fellow of the American Society of Animal Science in 1998 and received their Retiree Distinguished Service Award in 2019. He served as president of the Society for the Study of Reproduction in 1992-1993 and received its Distinguished Service Award in 2003. Keith was a Distinguished Alumnus of Potomac State College (2006) and was inscribed on the Duke Anthony Whitmore/Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Academic Achievement Wall there (2010). In 2007, he was named to the Hall of Honor at Petersburg High School and enshrined in the West Virginia Agriculture and Forestry Hall of Fame.

He also worked with ASI and the Sheep Heritage Foundation as one of the longest serving members of the review committee for the foundation’s annual scholarship.

He is survived by his wife of more than 60 years Ansusan Presby Inskeep of Morgantown; their sons, Todd Keith Inskeep (Deborah) and grandchildren Jennifer Michelle and Todd James of Charlotte, N.C., and Thomas Clower Inskeep (Rhonda) and grandchildren Olivia Gayle and Margaret Claire of Ellicott City, Md.; his brother, John Carter Inskeep (Deborah); sisters, Betty June Inskeep, Ellen Jane Inskeep (Larry); sister-in-law, Retta Presby Weaver, and many cousins, nieces and nephews and their families.